The Archive

A collection of earlier writings on history, religion, and geopolitics. These pieces reflect my broader academic interests prior to focusing on fundamental analysis and investing.

China’s Strategy in the Pacific

It is my belief that China’s desire for access to islands around the world is to harvest nuclear warheads in secret away from their mainland. This way, when China is done biding their time, they will be ready to show their strength to the “enemy troops…. outside the walls.”

Deng Xiaoping at the arrival ceremony for the Vice Premier of China (source, public domain via Wikimedia Commons)

This newspaper article was published in the Marshall Islands Journal on February 2nd, 2024. Below is the full article, along with the original clipping of the article from the newspaper:

In the late 1980s, rising inflation and political corruption in China led to increasing public criticism against China’s Communist Party leaders. This would eventually result in student-led demonstrations against the government in Tiananmen Square. Some students waged a hunger strike against the corruption, while others called for a new democratic government.

The then paramount leader of China, Deng Xiaoping, ordered tanks and troops to crush the protestors. The Chinese army fired into the unarmed crowds, while some protesters were crushed by tanks. In all, more than 2,000 died, ultimately destroying the movement for democracy in China.

The following year in 1990, Deng Xiaoping began to step away from leadership of China and left the next generation of Communist Party leaders a set of principles to guide them into the future. This 24-character instruction, as it came to be known, stated the following:

“Observe carefully; secure our position; cope with affairs calmly; hide our capacities and bide our time; be good at maintaining a low profile; and never claim leadership.” The explanation of this policy was then given in 12 characters, and its circulation was restricted to top party leaders. It read: “Enemy troops are outside the walls. They are stronger than we. We should be mainly on the defensive.”

When I read last week’s edition of The Marshall Islands Journal, I couldn’t help but to shake my head at the news of Nauru’s shifting diplomatic relations from Taiwan to China and to think about Deng Xiaoping’s instructions: “Secure our position… bide our time.” This just about summarizes China’s strategy in the Pacific.

In 2019, the Solomon Islands and Kiribati shifted their diplomatic relations from Taiwan to China. With Nauru now following suit, this leaves only three Pacific nations who still have diplomatic relations with Taiwan: the Marshall Islands, Palau, and Tuvalu.

And as of the time of writing this article, Tuvalu’s Prime Minister Kausea Natano, who favors strong ties with Taiwan, has lost his seat in elections, meaning that new lawmakers will meet within the week to vote for a prime minister. A pro-China prime minster could very well spell the end for Taiwan’s diplomatic relations with Tuvalu as well, making Taiwan’s diplomatic relations with the Marshall Islands that much more crucial.

It’s not just the Pacific islands that are important to China. It’s no secret that since 2013, China has been building and militarizing artificial islands in the South China Sea.

So if China is securing their position and biding their time with both the Pacific nations and with their man-made artificial islands, then this begs the question: “What for?” To answer this, I go back to Deng Xiaoping’s instructions: “Hide our capacities.” It is my belief that China’s desire for access to islands around the world is to harvest nuclear warheads in secret away from their mainland. This way, when China is done biding their time, they will be ready to show their strength to the “enemy troops…. outside the walls.”

Let’s not forget that it was Japan’s strength and occupation of the Pacific that emboldened them to attack Pearl Harbor in 1941 and drag the United States into the Second World War. Thus, Chinese strength in the Pacific could embolden them to do something similar, possibly with Taiwan or otherwise, in the not-so-distant future.

Published in the Marshall Islands Journal, February 2, 2024

What is Realpolitik?

I always looked up to Bismarck as the greatest statesman ever—a foreign policy genius who knew exactly what political moves to make, how to calculate each move, and how each move would play out. A part of me read the books in hopes that I would understand the “secret sauce” that made him such a foreign policy genius, and I found it.

Public domain cartoon of Bismarck and Pope Pius IX during the Kulturkampf

I always looked up to Bismarck as the greatest statesman ever—a foreign policy genius who knew exactly what political moves to make, how to calculate each move, and how each move would play out. A part of me read the books in hopes that I would understand the “secret sauce” that made him such a foreign policy genius, and I found it.

The reason why Bismarck was such a foreign policy genius was because he was a man who lacked political principles. As a matter of fact, Bismarck began his political career as a Prussian conservative. A conservative in the 1800s was one who believed in most of the following principles: first, in the obedience to the political authority of a monarch, second, in the opposition to individual rights or elected representatives for governments, third, that revolutions were a political evil, and fourth, that organized religion was crucial to order in society.

Public domain illustration of the execution of King Louis XVI during the French Revolution

Bismarck believed in the first principle, in the political authority of King Frederick Wilhelm I. But later in his career, he did not care for the other three. It was he who introduced universal suffrage in Germany, it was he who separated church from state and replaced clerical supervision in all public and private schools with state supervision, and it he who went so far as to defend political revolution. Here is Bismarck in his own words:

How many existences are there in today’s political world that have no roots in revolutionary soil? Take Spain, Portugal, Brazil, all the American Republics, Belgium, Holland, Switzerland, Greece, Sweden and England which bases itself on the consciousness of the Glorious Revolution of 1688…. (Bismarck: A Life, pg. 132)

This lack of principles eventually caused many of his fellow conservatives to distance themselves from him toward the latter half of his career. And it’s this lack of principles that makes Realpolitik possible. Here is a perfect illustration of this:

When Bismarck served as Prussia's envoy to the German Confederation in Frankfurt, he wrote to his conservative friend Leopold von Gerlach that it should be in Prussia’s interest to ally with the revolutionary France of Napoleon III. For a conservative of the 1800s, an alliance with a revolutionary republic—with an “illegitimate” emperor such as Napoleon III—was nothing short of scandalous. Gerlach, representing the Prussian conservatism of the day, wrote the following to Bismarck:

My political principle is, and remains, the struggle against the Revolution. You will not convince Napoleon that he is not on the side of the Revolution. He has no desire either to be anywhere else…. You say yourself that people cannot rely upon us, and yet one cannot fail to recognize that he only is to be relied on who acts according to definite principles and not according to shifting notions of interests, and so forth. (Bismarck: A Life, pgs. 131-132)

Bismarck, being no true conservative as Gerlach hinted at above, did not make decisions by any conservative principles. As a matter of fact, allying with revolutionary France was nothing but a rational calculation, one possible chess move among many for Prussia’s rise to dominance over Austria. And in a game of chess, it’s important for the player to have as many moves open to him as possible. As Bismarck observed years later:

My entire life was spent gambling for high stakes with other people’s money. I could never foresee exactly whether my plan would succeed…. Politics is a thankless job because everything depends on chance and conjecture. One has to reckon with a series of probabilities and improbabilities and base one’s plans upon this reckoning. (Bismarck: A Life, pg. 130)

This kind of cold, rational calculation lies at the heart of Bismarck’s Realpolitik, which has “nothing to do with good and evil, virtue and vice; it had to do with power and self-interest.” (Bismarck: A Life, pg. 130) The power of Prussia and the self-interest of Prussia is, in a nutshell, is how Bismarck conducted his foreign policy. And France was just one chess move among many to increase the power of Prussia and to destroy the power of Austria. As Bismarck wrote to Gerlach:

You begin with the assumption that I sacrifice my principles to an individual who impresses me. I reject both the first and the second phrase in that sentence. The man does not impress me at all…. France only interests me as it affects the situation of my Fatherland, and we can only make our policy with the France that exists…. Sympathies and antipathies with regard to foreign powers and persons I cannot reconcile with my concept of duty in the foreign service of my country, neither in myself nor in others…. As long as each of us believes that a part of the chess board is closed to us by our own choice or that we have an arm tied where others can use both arms to our disadvantage, they will make use of our kindness without fear and without thanks. (Bismarck: A Life, pg. 131)

This is Realpolitik. Whereas a conservative guided by conservative principles would not ally with France, thereby closing a space in a game of chess that would otherwise be open to him, a man who lacks principles has this space open as a possibility, thereby making him a more versatile and dangerous player in the international system.

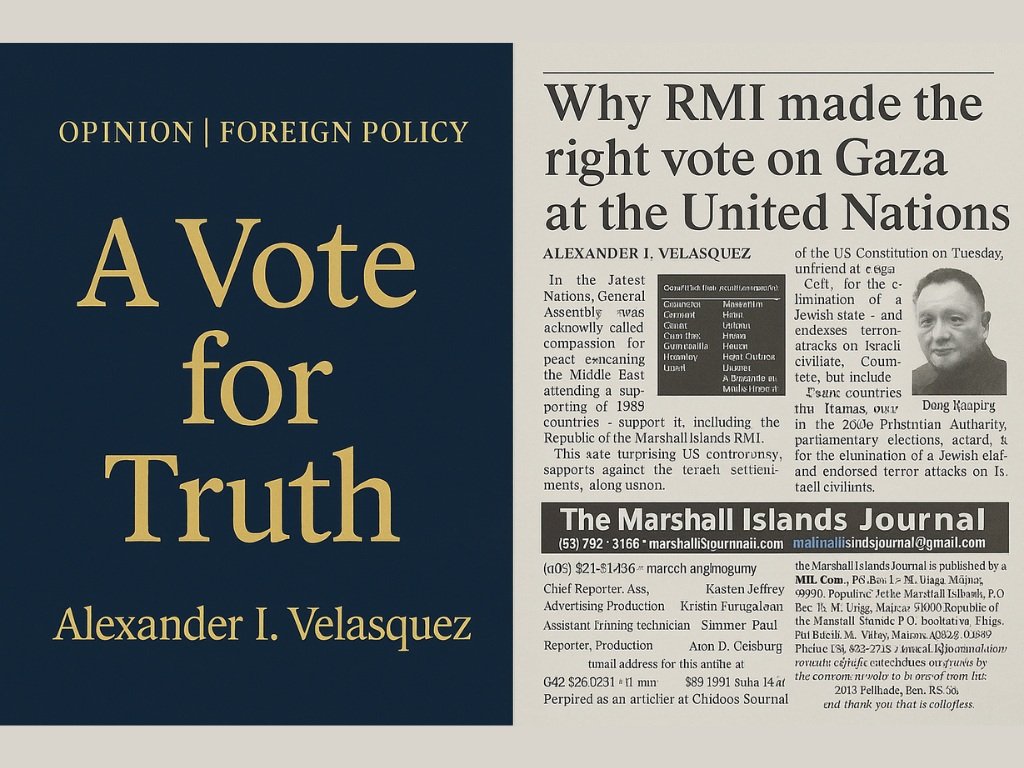

Why the Marshall Islands Made the Right Vote on Gaza at the United Nations

In last two editions of the Marshall Islands Journal, many contributors have expressed their disappointment at the RMI government in voting against a UN Resolution for a ceasefire in the ongoing war between Israel and Hamas. Here, I make the case that the RMI made the right vote.

Damage in Gaza Strip during October 2023 (source via Wikimedia Commons)

This newspaper article was published in the Marshall Islands Journal on November 17, 2023. Below is the full article, along with the original clipping of the article from the newspaper:

In last two editions of the Marshall Islands Journal, many contributors have expressed their disappointment at the RMI government in voting against a UN Resolution for a ceasefire in the ongoing war between Israel and Hamas. I want to make the case that the RMI made the right vote.

First, there seems to be this strange idea going around on social media and even in the press that the state of Israel is “occupying” or “colonizing” the Palestinians on their rightful land. But, historically speaking, that is not true.

Map of the Ottoman Empire in 1914 (source via Wikimedia Commons)

The territory of Palestine in the early 1900s belonged to the Ottoman Empire. When the Ottomans were defeated in the First World War, the victors—Great Britain and France—governed the former Ottoman territories with supervision from the newly created League of Nations. These European nations then created the states of the Middle East that we know today, including Palestine, Lebanon, Syria, and Iraq. The Arabs of these territories didn’t even identify with these newly created borders drawn up by Europeans—the only thing they had in common was that they were all Arabs who were formerly subjects of the Ottoman Empire.

League of Nations mandates after World War I (source via Wikimedia Commons)

But by 1917, one year before the end of the First World War, Britain’s Balfour Declaration stated its intention to support a national home for the Jews. And it was this declaration that drew the Jews to Palestine. Many Jews who were persecuted in Nazi Germany then fled to Palestine—and who could blame them? By 1939, there were already 450,000 Jews in Palestine. And after the Second World War, the world began to learn about the Holocaust: Hitler’s deliberate extermination of six million Jews by execution squads and death camps. This sympathy for the Jewish plight led the United Nations to divide Palestine into both the Jewish state of Israel and the Arab state of Palestine in 1948.

The Balfour Declaration (1917) (source via Wikimedia Commons)

Knowing all of this, how can anyone say that the Jews are occupiers or colonizers? They simply took advantage of a situation where the governors of their biblical holy land offered them refuge and the opportunity to settle in the region to have own nation—and they took full advantage of it.

Second, this war is not between Israel and Palestine; it is between Israel and Hamas. Hamas is a terrorist organization, and their main goal is to destroy Israel and replace it with one Islamic Palestinian state. They are supplied with a large number of weapons and money from Iran, whose president in 2005 described Israel as a “disgraceful blot” that “must be wiped off the map.”

Iran’s views have since not changed. After Hamas’ surprise attack on October 7, a day for the Jewish Sabbath and a Jewish High Holiday, the Iranian Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei said: “We support Palestine and its struggles… This attack is the work of the Palestinians themselves, and we salute and honor the planners of this attack.”

And Hamas is to blame for why the United Nations is having such a hard time delivering aid. Israel knows that Hamas will take that aid, especially the petrol, for its military instead of using it on hospitals and water desalinization.

Since taking power in Gaza in 2007, Hamas has shown that it cares nothing for the Palestinian people. In the last 16 years, they have done nothing to alleviate the Palestinians from high levels of poverty and unemployment, and they knew that it would only be a matter of time before they were discredited by their political rival: The Palestinian Authority. The only way Hamas could gain points over their rival was to do something to make it seem as if they were making some sort of progress, and the method they chose was to attack Israel. The result is the ongoing war that has destroyed the lives of innocent civilians on both sides. But that did not seem to matter to Hamas because, to them, political power is more important than the lives of their own people.

Since Hamas cares nothing for the Palestinians, it makes no sense to send them aid in hopes that, somehow, they will use it responsibly; if anything, it sounds like wishful thinking.

Published in the Marshall Islands Journal, November 17, 2023

Review of Appeasement by Tim Bouverie

Tim Bouverie wrote the authoritative book when it comes to Neville Chamberlain’s failed policy of appeasement in the 1930s. After getting through this masterpiece of a book, I had to stop and ask myself: “How did the British refrain from placing Chamberlain’s head on a spike?”

Cover of “Appeasement” by Tim Bouverie, photographed by Alexander I. Velasquez

Book Details

Category: Non-fiction, history, international diplomacy

Page Count: 419 (Paperback Edition)

Year of Publication: 2019

Rating: 5/5

10-Word Summary: The diplomatic history of Neville Chamberlain’s failed policy of appeasement.

About Appeasement

Tim Bouverie wrote the authoritative book when it comes to Neville Chamberlain’s failed policy of appeasement in the 1930s. After getting through this masterpiece of a book, I had to stop and ask myself: “How did the British refrain from placing Chamberlain’s head on a spike?”

Appeasement begins with Adolf Hitler’s ascension as Chancellor of Germany in 1933. The British press didn’t know what to make of Hitler; The Times claimed he “was held to be the least dangerous solution of a problem bristling with dangers,” while The Economist, the Spectator, and the New Statesmen foolishly stated: “We shall not expect to see the Jews’ extermination, or the power of big finance overthrown.” (Pages 8-9) The French press was equally clueless, and reading all this gave me the realization that newspapers, in general, are terrible sources for geopolitical information, as journalists usually guess as to what a world leader is really up to, and their guesses do not constitute knowledge any more than the average person on the street who guesses correctly which side a six-sided die will fall on.

As for the policy of appeasement itself, Bouverie gives a wonderful explanation as to why it was the foreign policy of choice for Britain throughout the 1930s: The Allies believed that they were to blame for the rise of the Nazi Party; as a matter of fact, Nazism was “the natural, if violent, reaction to legitimate grievances stemming from Versailles.” (Page 48) At this point, the Treaty of Versailles had come to be viewed a treaty that was too harsh, hence the idea was that “the Treaty should be altered and Germany allowed to regain that place and status to which her size and history entitled her.” (Page 48) The only problem with this policy is that it assumed Hitler could be appeased, and few people saw Hitler for who he really was.

Mein Kampf

Anyone who reads Mein Kampf will be baffled at how open Hitler was in stating his foreign policy ambitions: He announces his desire to unite Germany with Austria, he announces his desire to expand Germany’s territory at the expense of Russia, who he refers to as a “culturally inferior” nation, and he announces that the French were the mortal enemy of the Germans. Hitler said the following about France:

Never suffer the rise of two continental powers in Europe. Regard any attempt to organize a second military power on German frontiers, even if only in the form of creating a state capable of military strength, as an attack on Germany, and in it see not only the right, but also the duty, to employ all means up to armed force to prevent the rise of such a state, or, if one has already risen, to smash it again. (Mein Kampf, Page 664; First Mariner Books Edition)

All of this begs the question: With Hitler’s foreign policy of territorial conquest out in the open, why did the British choose the policy of appeasement? If anything, one would think that the British leaders would favor to formulate some sort of Bismarck-style alliance system with France, the Soviet Union, Poland, and Czechoslovakia in an attempt to keep Hitler from conquest.

But Bouverie makes it clear that the British chose appeasement for the same reason we in the 2020s would chose appeasement if Adolf Hitler were around today: No one read Hitler’s book. And those that did read his book were of split opinion: Since Hitler was proclaiming that he was “a man of peace” early in his chancellorship, those that believed him dismissed his early writings as the “the moribund rantings of a young firebrand.” (Page 18) Even Neville Chamberlain, who had read excerpts of Mein Kampf, chose to ignore Hitler’s early writings, stating: “If I accepted the author’s conclusions I should despair.” (Page 418) This brings me to my final point and the main character of Bouverie’s book: Neville Chamberlain.

Neville Chamberlain

To be fair, I don’t want to put all the blame on Chamberlain, as Bouverie makes it clear that appeasement had already been the policy of choice for both the government and, more importantly, for the British people. Stanley Baldwin, who preceded Neville Chamberlain as Prime Minister, admitted that even if he were to go back in time and try to convince the British populace that Germany was a threat and that Britain should focus on rearmament in the midst of an economy attempting to get out of the Great Depression, the effect would have been disastrous and have meant the loss of a General Election. (Pages 25-26) Indeed, it was Winston Churchill’s pursuit of rearmament that made him so unpopular in the 1930s until his eventual ascension to Prime Minister in 1940.

By the time Neville Chamberlain became Prime Minister in 1935, his main goal was to balance the budget and cut expenses to get Britain out of the Great Depression; but he just so happened to take the job at the same time Hitler’s rearmament program was in full swing. Eerily, it was Chamberlain’s half-brother Austen Chamberlain who had reminded Neville after a dinner in 1936: “Neville, you must remember you don’t know anything about foreign affairs.” (Page 129) That statement turned out to be prophetic, as the rest of the book details how poorly Chamberlain handled the international situation. To make things worse, Chamberlain was hard-headed, always convinced that he was right. For example, his desire to appease Benito Mussolini’s aggression in Ethiopia would eventually lead to the resignation of his Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden, all of which Bouverie brilliantly details in chapter ten. Chamberlain even went so far as to have secret channels of communication with Mussolini so as to not have to go through his secretary—an obvious sign that Chamberlain felt he could handle the international situation himself without the need to seek advice from any members of his cabinet. And when you couple Chamberlain’s stubbornness with the fact that he surrounded himself with “yes men” who were convinced that appeasing Hitler’s desires for German greatness was the right policy to pursue, what you get is a recipe for disaster.

Should You Read Appeasement?

The answer is a definite yes. Tim Bouverie’s first book is both a classic and a must-have for those who are interested in history—in particular the diplomatic history leading up to the Second World War—and the best source for explaining why Britain’s policy of appeasement failed to stop Adolf Hitler in his pursuit of empire. Bouverie does a wonderful job weaving the policy of appeasement in the 1930s into one dramatic narrative, and, if you can, read the book along with the audiobook narrated by John Sessions. Sessions did an amazing job narrating and deserves an equal amount of praise for his performance.

Review of Munich, 1938 by David Faber

I really don’t like this book; I’m just going to state it from the beginning. I will never write a review for a book having read only half of it—in this case 230 pages. For me, I have to read the entirety of a book to write a good and comprehensive review. But I’m willing to make an exception for one simple reason: The title is completely misleading.

Photo by Alexander I. Velasquez (author’s copy)

Book Title

Category: Non-fiction, diplomatic history, politics

Page Count: 504 (Paperback)

Year of Publication: 2010 (Simon & Schuster Reprint Edition)

Rating: 1/5

10-Word Summary: A detailed diplomatic history between Britain and Germany from 1937-1938.

About Munich, 1938

I don’t like this book; I’m just going to state it from the beginning. I will never write a review for a book having read only half of it—in this case 230 pages. For me, I have to read the entirety of a book to write a good and comprehensive review. But I’m willing to make an exception in this case for one major reason: The title is completely misleading.

The title is Munich, 1938: Appeasement and World War II. Yet, Munich 1938 gets one or two chapters at the end of the book. And I get it: Faber is writing the buildup to Munich 1938 and all the diplomacy that preceded it. But Faber starts his account from November 1937. Why on earth would anyone start at November 1937? The logical place would be to start at 1933 because that is when Hitler comes to power and assumes the chancellorship in Germany.

Also, to understand Munich 1938, one would have to understand Hitler’s foreign policy ambitions and, hence, understand what lies in the pages of Mein Kampf. Yet, Faber never mentions Hitler’s famed book or even references his ultimate foreign policy objective of fighting the Soviet Union and destroying France. And because Faber starts his account so late in 1937, it’s impossible to understand why Hitler is even invading Austria and Czechoslovakia in the first place.

What about appeasement? Appeasement is never fully explained. Faber makes it clear that Chamberlain wanted to appease Hitler but not why he wanted to appease Hitler.

What about World War II? Everything in the book happens before World War II. I have no idea why World War II is even part of the title of this book.

The real title of this book should be: A detailed diplomatic history between Britain and Germany from November 1937 to October 1938; that’s all this book is. And I’m upset because I bought this book to understand appeasement, to understand why Chamberlain trusted Hitler’s promise at Munich, and to understand those who opposed appeasement. After all, appeasement is in the title of the book. You would think things like this would be explained. But no. I got none of that.

There are also so many people in this book—too many as a matter of fact. Because Faber condenses a dramatic eleven month history of diplomacy, his account is overly detailed and has so many people involved that it is easy to forget who most of them are outside of the major players in the account such as Hitler, Chamberlain, Eden, and so on. It makes for a very frustrating read having to constantly ask the question, “Wait, who is this again?”

Just about the only positive thing I have to say about this book is that Faber does know his stuff, and he gives a very detailed account of all of the diplomacy, both secret and public, that went on in both Hitler’s and Chamberlain’s cabinet from 1937-1938. Otherwise, this book was completely useless for me.

Should You Read Munich, 1938?

If you are looking for a book that will explain appeasement—what it was and why it became Britain’s foreign policy, the conflict between Chamberlain and Churchill, and the road to World War II, read Appeasement: Chamberlain, Hitler, Churchill, and the Road to War by Tim Bouverie (a review for this is coming soon). However, if and only if you are looking for an extremely detailed diplomatic history between Britain and Germany from November 1937 to October 1938, then this is definitely your book.

Review of The Clash of Civilizations by Samuel P. Huntington

Samuel P. Huntington’s The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order is one of the greatest books I have read in my life. Sometimes I would just shake my head and pause my reading because I had to think about whether Huntington was some sort of fortune teller given how eerily accurate his prediction of the 21st century geopolitical landscape was when he published his book back in 1996.

Photo by Alexander I. Velasquez (author’s copy)

Book Details

Category: Non-fiction, political science, national & international security, international relations, international diplomacy

Page Count: 352

Year of Publication: 2011 (Paperback Edition)

Rating: 5/5

10-Word Summary: Civilizations have replaced ideologies as the driving force of geopolitics.

About The Clash of Civilizations

Samuel P. Huntington’s The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order is one of the greatest books I have read in my life. Sometimes I would just shake my head and pause my reading because I had to think about whether Huntington was some sort of fortune teller given how eerily accurate his prediction of the 21st century geopolitical landscape was when he published his book back in 1996.

Huntington was the Albert J. Weatherhead III University Professor at Harvard University and chairman of the Harvard Academy for International and Area Studies. He was also director of security planning for the National Security Council in President Jimmy Carter’s administration, as well as the founder and coeditor of Foreign Policy.

The Clash of Civilizations is divided into five parts: Part I covers the first three chapters where Huntington argues that the most important distinction between peoples in the post-Cold War world is civilization and not ideology. For example, World War II was an ideological war featuring German Nazism, Italian Fascism, and Soviet Communism, while the Cold War was an ideological battle between the Communist East led by the Soviet Union and the capitalist West led by the United States. But after the collapse of the Soviet Union, the age of ideologically driven geopolitics had come to an end and was replaced with what Huntington proposes is the new paradigm of geopolitics going into the 21st century: civilizations. And the most important element of civilizations, that which divides nations and populations more than any other element, is religion.

Hence, in Part II, Huntington details that the upcoming geopolitical conflicts will be between civilizations due to the religious, and therefore political and cultural, differences. For example, the late 20th century featured the Islamic Resurgence, where Arab governments turned to Islam to enhance their political and spiritual authority and to gather popular support. The Iranian Revolution from 1978-1979 is the most famous example of this. Islamic law replaced Western law, Islamic codes of behavior, such as the banning of alcohol and proper female covering, replaced Western codes of behavior. But the interesting thing Huntington points out is that here in the West we call this Islamic “fundamentalism.” The irony is that these Islamic laws come from the prophet Muhammad himself, either from the Qur’an or from the hadith: the sayings and practices from the prophet Muhammad. If the Qur’an is supposed to be the literal word of God as Muslims believe it to be, then not following Islamic law is not following the will of Allah. All this to say that there is no middle ground: Western values inherently clash with the will of Allah.

Yet, the main idea in Part II is not necessarily the clash with Islam. Rather, the main idea is that the West is in decline—both in influence and military power. Henry Kissinger eerily says the same thing in Diplomacy, another famous book published two years earlier in 1994, where Kissinger also predicts how the geopolitics of the 21st century will be shaped.

Not only is the West in decline, but rapid economic development in Asia beginning with Japan in the 1950s and continuing into the mid-1990s with the rapid economic growth in China meant another threat to the West in the form of a Chinese-led world order in East Asia. Given Asian belief that Asia will surpass the West economically, growing Asian belief in the cultural superiority over the West, and the need for Asian nations to find common ground in Asia, it was clear to Huntington that Asia and its values will threaten the weakening Western-led world order.

This leads into Part III, where Huntington explains that the international relations of the 21st century will revolve around countries grouping themselves around the lead states of their civilizations. For example, the West, though in decline, will continue to be led by the United States, while East Asia will rally around the leadership of China, and the Baltic and Orthodox states will unite around Russia.

And in Part IV, Huntington explains that the West’s desire to maintain its military superiority through policies of nonproliferation and counterproliferation and the West’s desire to spread political values such as democracy and human rights will inevitably lead to conflicts with Islamic governments and East Asian governments. This is why Bill Clinton failed to halt the North Koreans from acquiring nuclear weapons and why the Japanese government distanced themselves from the United States’ human rights policies in the 1990s.

Part V ends the book on a somber note: The United States must affirm and preserve its Western identity and create stronger relations with other Western nations based on similar cultural and religious heritage. But the West must “Recognize that Western intervention in the affairs of other civilizations is probably the single most dangerous source of instability and potential global conflict in a multicivilizational world”(Page 312). Hence, it’s best to leave China to East Asia and leave the Baltic states to Russia.

Should You Read The Clash of Civilizations?

I cannot do this book justice in a 1,000-word review. I have tried to summarize the book through the narrative of international relations, but this book is so much more than that. For example, Huntington discusses in great depth the civilizational conflicts that happen within the borders of one nation, such as the ones that happened in Yugoslavia—a conflict among the Catholic Croats, the Bosnian Muslims, and the Orthodox Serbs. And he discusses the problems that lead to decay within a civilization, such as the growth in crime, the growth in divorce, and the weakening of the work ethic.

If someone who knew nothing about geopolitics or international relations could only read one book to understand everything happening in the 21st century, I would say that this is the book to read. Huntington’s writing is great, he backs his assertions with great detail, but most importantly, his analysis is proving to be correct.