The Tulip Bubble (1636–1637): The Flower That Fooled Europe

The Tulip Folly by Jean-Léon Gérôme (1882). Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

🌷 The First Financial Frenzy

Imagine working for an entire year only to spend all of your money on a single flower bulb.

In the winter of 1636, that’s exactly what some Dutch traders were up to because tulips had become the hottest investment in Europe. There were merchants, artisans, and even some lower-class individuals making bets on flowers that hadn’t even bloomed.

But beneath the bright, fragile, and colorful petals was a dangerous illusion: the belief that prices would never fall. And within months, the markets that had captivated speculators in key cities had collapsed within weeks. There was confusion, there was disbelief, but, most importantly for us investors today, there was a lesson to be learned in what is now known as one of the most famous cautionary tales in financial history.

This is the story of the Tulip Bubble: the first recorded speculative mania and, to this day, one of the most misunderstood.

Semper Augustus (Anonymous, 17th century). Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

📜 Historical Breakdown: How It All Began

The tulip had first arrived in Europe from the Ottoman Empire in the mid-1500s. By the early 1600s, the Netherlands, which was already a wealthy and innovative nation, had fallen in love with them. The Dutch elite prized these flowers for their beauty; but, most importantly, they prized them for what they represented: rarity, refinement, and wealth.

Among the many varieties, there was one that stood out among the pack: the “broken bulbs.” It was these that produced extraordinary multicolored flowers that included streaks of red, yellow, and purple. The irony is that, unknown to the gardeners at the time, this was caused by a virus that had infected the bulb and resulted in an unpredictable pattern on the tulip that could never be replicated. And, since these flowers were valued so highly for their rarity, the rarer the pattern, the higher the price.

By the 1630s, Amsterdam’s merchant class had become flush with cash from their global trade. This, in combination with low interest rates, meant that investors were hungry for new opportunities. And tulip bulbs, of course, were the perfect commodity for this milieu: they were physical, they were scarce, but—best of all—their prices were always going up.

As demand grew for the tulip grew, so too did it grow as a status symbol: It became an asset to trade and even to speculate on. And what began as a passion for beauty was now slowly morphing into an obsession for profit.

Still Life with Flowers by Hans Bollongier (1639). Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

💡 The Mechanics: How the Bubble Formed

Economists today call this kind of event an asset price bubble: when the price of something rises far above its reasonable value—or what we analysts like to call “fundamental” value—and it rises for one reason: simply because people expect it to keep rising.

But figuring out what is a “reasonable” or “fundamental” value isn’t easy, even in today’s stock market, let alone in the 1630s where there were no spreadsheets, valuation models, or market data. People simply relied on their gut feeling, on gossip, and on the hope that someone else would pay more for their asset tomorrow.

In the case of the tulip, there was a small, but genuine increase in demand that triggered the whole frenzy: a fashion trend. Dutch women were decorating their gowns with exotic flowers, and now tulips were suddenly in style, literally. And with the tulip in style, their demand had risen. Prices climbed as people scrambled to buy the rarest of bulbs.

Then, something happened in the market that changed everything: Tulips had become so valuable that people couldn’t afford them to trade them directly. So, instead of buying actual bulbs, traders began to make promises to buy or sell bulbs in the future. Turns out that this was the earliest form of what is now known as a futures contract.

These contracts were informal and were often made in taverns (of all places). There was no cash exchanged between hands, and no one was required to deliver the tulips later. The buyer and the seller agreed on a future price for a specific bulb type. For example, the buyer might say: “I’ll buy one pound of Admirael van der Eijck bulbs in March for 1,000 guilders,” to which the seller could agree and even resell that contract to someone else at a higher price to make a profit without ever touching the bulb.

People who had never touched a tulip had now joined the fray: bakers, butchers, and even sailors became speculators overnight. I mean, why work for slow wages when a single tulip trade could make you rich?

And at the peak of the mania, a rarest of bulbs had a higher value than a canal house in Amsterdam (around 5,000 to 10,000 guilders). Even ordinary tulips that were once sold by the pound were now changing hands for around 10 to 100 Dutch guilders.

The psychology was intoxicating to say the least. Everyone believed they could sell their tulip to the “greater fool.” One historian put it this way: “It was not the flowers that were traded, but the wind.”

Tulip Mania by Johannes Hinderikus Egenberger (19th century). Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

🫧 The Pop: When the Fantasy Ended

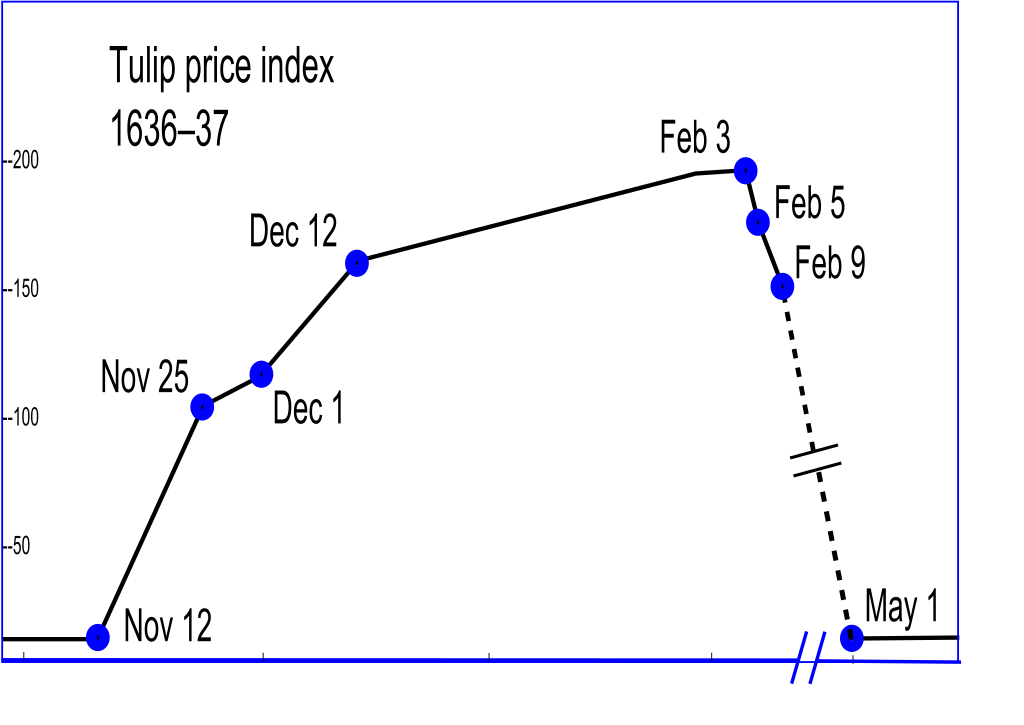

Then, in February 1637, it all stopped.

To this day, no one knows exactly what triggered the crash. It could have been because prices had grown too high for new buyers to enter. Or maybe it was because a few traders began to cash out, in turn spooking those who hadn’t yet done so, and there were no new buyers. Or perhaps it was the rising doubts about the legal enforceability of the futures contracts.

Whatever the cause, the panic had spread.

In just a matter of days, buyers had vanished. Sellers rushed to unload their contracts, but there were no takers. Prices that had risen for what had been months collapsed within weeks. The tulip that had once sold for thousands of guilders was now virtually worthless.

But here’s the twist: despite the pop, the economic fallout was surprisingly small. This was because most tulip “trades” were made with little to no real money down. In other words, there wasn’t a massive loss of real wealth; rather, it was the paper promises that had evaporated.

Now there were stories of ruined speculators, but there is no evidence of a national economic depression or a banking crisis or anything of the sort. So, the Dutch economy, which was driven by trade and finance, continued mostly unharmed.

But there was embarrassment for those who participated, especially because the Dutch were proud of their thrift and rationality. How could they allow such a mania to take ahold of them?

Unbeknownst to these economically advanced people of the 17th century, this episode was nothing more than a revelation of human nature and behavior: greed, pride, and the madness of crowds. It is a warning that echoes even to the present day.

Photo Credit: JayHenry, Tulip Price Index (1636–1637), CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

🔮 Modern Parallel: From Tulips to Tokens

We might laugh at 17th century traders gambling on flowers thinking that they didn’t know any better, but are we really so different?

In 2021, millions of investors poured into cryptocurrencies, meme stocks, and NFTs for the same exact reason the Dutch bought tulips: because prices kept going up. (Or, as the meme phrase goes: Stonks only go up.) Digital images of cartoon apes sold for millions, thousands of cryptocurrencies were launched, and while some of them promised revolutionary potential, most were outright scams.

Just like the tulip traders in the taverns who speculated through easy-to-make futures contracts, the speculators of 2021 often used easy-to-have leverage alongside cash investments (I know I did) for promises of future value. And when the sentiment turned in November 2021, the entire crypto market lost over two trillion dollars in value within months.

Technology and modern assets are now more advanced, but human psychology has not changed. Markets are not ruled by math alone—they are powered by hope, fear, and narrative. Unfortunately for the Dutch, the narrative that tulip prices can only go up was sorely mistaken. When prices detach from reality, fundamentals no longer matter; everything becomes about momentum. And the thing about momentum is that it never lasts forever.

Flora’s Wagon of Fools by Hendrik Gerritsz Pot (c. 1637). Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

🧠 The Lessons Beneath the Petals

The Tulip Bubble reveals something timeless about human nature and markets:

Bubbles start with truth. Here’s the thing: There really was new demand for tulips, just as there was real innovation and demand behind the internet during the dot-com bubble. But enthusiasm can quickly turn into speculation when people stop asking why prices are rising and simply assume that prices must continue rising.

Uncertainty fuels manias. No one knew how to value tulips, just as few today can confidently value a new cryptocurrency or an NFT. When people don’t know what something is worth, emotion drives value, and it sets a dangerous precedent.

Easy money accelerates danger. Futures contracts in taverns had the Dutch speculating without any real risk. Think about this in our time: margin debt and leverage allow people to borrow money with ease, and when it costs almost nothing to bet, too many people will. (I don’t think it’s a coincidence that the stock market boom from 2020 to 2021 coincided with the issuance of stimulus checks during and after the pandemic.)

Bubbles always end abruptly. Once prices stop rising, the illusion breaks. The same forces that inflate the bubble—FOMO, momentum, and herd behavior—now work in reverse.

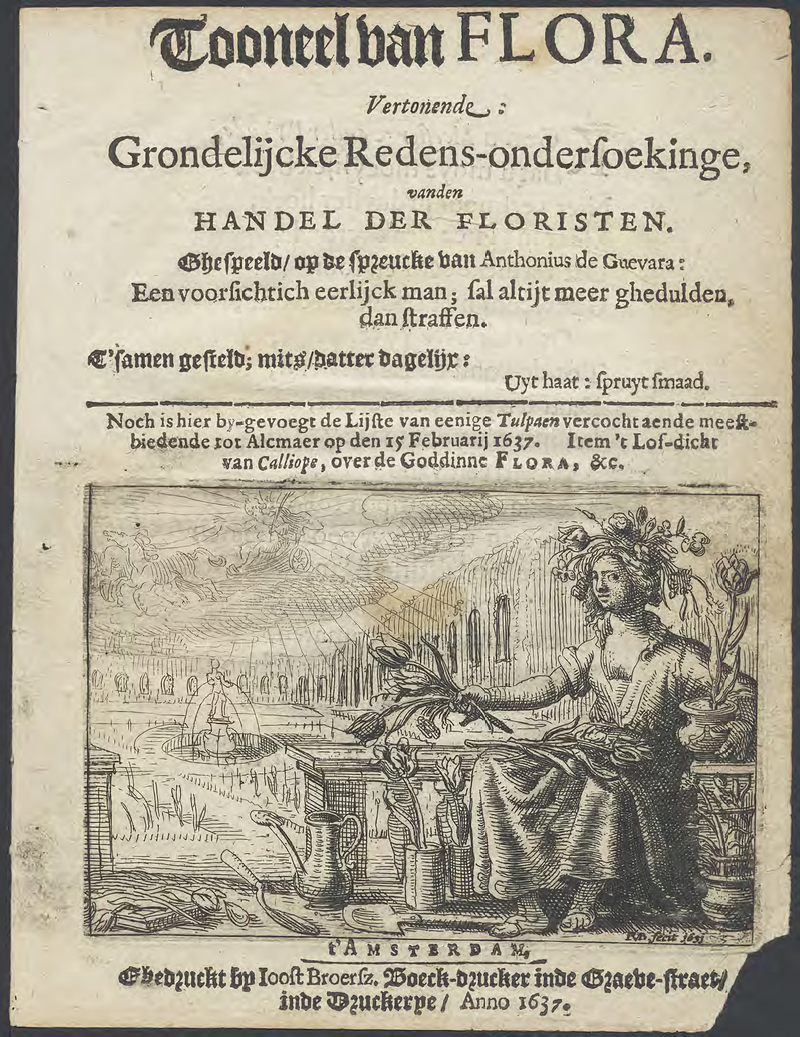

Tooneel van Flora (1637), an Amsterdam pamphlet documenting the tulip trade and speculative frenzy during the Dutch Tulip Mania. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

💬 Investor Takeaway: What Smart Investors Can Learn

For us investors today, the lesson from the Tulip Bubble is simple yet profound:

Never confuse excitement with value.

A bubble thrives when investors stop asking, “What is this worth” and instead start asking, “How much higher can it go?” The moment you buy an asset because everyone else is doing so is the moment you’ve lost perspective and joined the herd.

Now, don’t misunderstand me: This doesn’t mean you should avoid all emerging trends—because you shouldn’t. Every major opportunity for wealth—from railroads to electricity, down to the internet and the concept of a digital currency—began with a speculative phase. But you must differentiate between lasting innovation and temporary mania.

For example, take digital currency: I don’t believe digital currency is hype. But, let’s just be honest: It’s mostly speculation; while some cryptocurrencies provide genuine innovation, the majority of cryptocurrencies and tokens are outright scams. They key is to always go back to the fundamentals, even for crypto. Before you invest in the “next big thing,” ask three major questions:

Does this asset produce or represent real value?

Are buyers motivated by the asset’s use or utility?

Could I still justify the purchase, or would I buy more, if the stock or asset dropped by 50%?

If the answer to any of these questions is no, then you might just be speculating. And history always shows that speculation, no matter how exiting or exhilarating, always ends the same way.

📚 Attribution: Adapted from Lecture 4: “The Tulip Bubble,” taught by Professor Connel Fullenkamp in Crashes and Crises: Lessons from a History of Financial Disasters (The Great Courses, Duke University).

🔗 Internal Links:

Next in the series: South Sea Bubble (1720): Lessons from Britain’s Historic Financial Crash